Stacy Elaine Dacheux: I recently read in The New York Times Magazine about an art student named John Powers who worked in the studio for Jeff Koons in 1995. At one point, Powers suggests his job was comparable to filling in a “paint by numbers”– except this particular “paint by numbers” titled “Cracked Egg” sold for $501,933 at Christie’s. What are your thoughts on this article or this practice Koons employs? Also, how does it conceptually relate or not relate to your own work?

Jennifer Jarnot: I see little relationship between my work and the article, or to Jeff Koons’ work in general. First, my thoughts on the article. It seems that Mr. Powers most certainly knew what he was getting into when he signed on to work in Koons’ studio, and his subsequent motivations and travails can be clear only to him.

My personal feeling is that I have no objections to this “factory-oriented” form of artistic production, nor to the tailoring of the stylistic and mechanical aspects of the work to allow it to be completed by assistants. Having the work completed by assistants does not demean or compromise Mr. Koons’ artistic vision in any sense of the word. And, it seems that Jeff Koons and/or his work has become a brand as much as anything else. It is what it is because of what it is.

In terms of the concept of studio assistants, it is similar to the musician who needs a skilled back-up band, or in the case of recording, a talented producer or the great novelist nearly always relies heavily on the services of an amazing editor (s) to help to put the idea across, not to mention agents and all the other people who assist the artist in getting one’s work into the world. In the case of the visual artist, there are agents, aka galleries and, depending on one’s financial situation, studio assistants in terms of different aspects of construction, etc. It is well known that artists throughout history have relied on studio assistants at every level of studio production from underpainting to even a final rendering.

In fact, could I afford to do so, I would certainly consider hiring and training an assistant to apply paint to some of my paintings where applicable. However, I am not willing to cede control of the color mixing, and my approach to the final product is somewhat organic and intuitive and is often subject to change as I work my way through a painting. Many times I know I have the correct color only when I see it on the canvas.

Disregarding content and pop culture, I think Mr. Powers’ description of the Koons’ painting being similar to a paint-by-number is the only conceptual similarity to my work. In the case of the Koons, surfaces are necessarily broken into minute and intricate planes in order to allow them to be “painted in” by others.

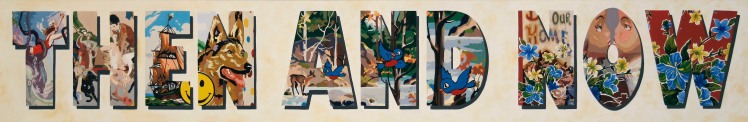

My work does borrow heavily from paint-by-number paintings, but is more about the “look” of the paint-by-number as a cultural icon. I cherish this look on two levels; first as a low-brow object (PBN) that was never revered, valued or collected, and second as a very common method for the reduction and abstraction of an image down to essential shapes and colors, thereby ridding the work of the excessive virtuosity of traditional rendering.

I realize full well that there are many among us who do not appreciate the true genius and immediacy of the paint-by-number, but (for me) it has become the perfect borrowed style with which to marry style and content – the content, my fascination with for the nostalgia of popular culture, particularly the stuff of one’s childhood when learning was largely experiential and not imposed.

Stacy: Why do you think we, the collective universal we, are so protective about art– what it is or what it is not? Does nostalgia play a role in this?

Jenn: If I knew the answer to that, would I be the smartest person in the world? Oh wait, then we would have to define “world.” And how should we do it, in terms of size, category, and list the many worlds representative of disciplinary boundaries, i.e., art world, sports world, fashion world, ad infinitum?

Seriously, this question is so huge and would require a book to flush out, in that it necessarily ventures into the realm of preciosity/preciousness, politics, status and the marketplace. So I have as many questions as answers.

Superimposed over everything is the collector instinct, or some might say, the hoarder instinct. I think we all have it to some degree or another.

I am always amazed when I learn that certain collectors are willing to spend exorbitant amounts of money on vintage cars, hood ornaments, guitars, old toys, or tupperware, only to learn that they do it obsessively, and have at least a “hundred of them.” And is that all because we just have way too much money, or is it some innate insecurity that keeps us coming back for more? I am guilty myself. I have a huge number of original paint-by-number paintings. I justify my continued purchases as contributions to my well being, i.e., they make me happy and I love to look at them. And here, I suppose, is where nostalgia comes into play. Generally speaking, we collect what has been, as opposed to that person who fills their second bedroom with gum wrappers, bottle caps, or bent nails.

Actually, looking out my window I just saw a squirrel scamper up a tree with an acorn or something in its mouth, and it makes me wonder if there is that squirrel out there who, when putting up nuts for the winter, thinks, “oops, gotta run out! Think I can squeeze about thirty more in over here in the corner. And, yeah, there is a little space on the end of that shelf, and all the nuts I have are light brown. I need some of the dark ones.” If that’s true then nature trumps nurture once again. Bet there are no squirrels doing performance art.

In terms of being protective about what art is or is not, we are naturally more wary, I think because art is more ephemeral and less concrete, i.e., we just don’t understand it really, never have, never will. Also, not unlike the automobile collector, art is a status symbol, and it becomes so by the way of the tastemakers, the dealers, promoters, curators, etc. I don’t think there is one of us who doesn’t harbor somewhere the notion that this or that well-collected artist’s work is the personification of the “emporer’s new clothes.” And, the reality is all along that ascendancy of tastemaking, people are making a name for themselves as well. Not being an expert by any means (again I just make the stuff), I know there are dealers and curators who put their reputations, hence their careers, on the line in the promotion of a given artist. No one likes to lose.

Collectors on the other hand, while probably obsessive-compulsive like all the rest of us in the collector realm, have to be aware of the investment aspect of collecting. That overlays back across the status thing also in terms of original price and now it is worth twice as much. However, not to demean the art collector, I think they come in several categories. There have to be those who collect what they collect because they are told to by a dealer, and often designers, and have no idea if they like it or not. The same is probably true for the rest of their furnishings. Then there are the collectors who love art and who are artists themselves, like Steve Martin. Then there are those who also love art, but have the altruistic desire to make it available to the public, like Alice Walton. As an artist, I say bless them all.

Finally, there is also the awful truth that, in hard times, the first things to be “cut,” at every level, are the arts. Sometimes I think that the general public could care less about any of it and merely tolerates it, will most certainly take the kids to museum or a puppet show once in awhile, but those are just things that are there, and should be there, and it’s a lot cheaper than taking the whole family to a game. But you’d better not use my tax dollars to pay for it. That’s where the art world becomes an elitist enterprise out of necessity really. It takes at least some small amount of courage to stand outside the deep, often perilous waters of the mainstream.

BTW, I didn’t really even discuss preciousness, but it is most certainly implied throughout. The idea that there will never be another one due the age or the demise of the artist, or the thought of bidding wars because everyone wants the same thing is well beyond my level of expertise and probably is best analyzed, or even speculated upon (no pun intended) by marketing experts or social historians.

Stacy: I like that you mention Steve Martin– it made me think about your ukulele pieces. What inspired you to paint on this specific type of instrument? It seems to be the perfect whimsical canvas to explore your passion for collecting and depicting nostalgia.

Jenn: Yes, I also thought the ukuleles were the perfect format. It seems that the ukulele nearly always elicits a giggle or two, although not from me. I talk about the connection in the latest version of my artist statement:

Leisure time was a new concept during the 1950’s and paint-by-number kits were a wildly popular hobby craze that made the successful creation of a painting available to everyone. With the purchase of an inexpensive painting kit, one did not have to worry about composition, subject matter, or the analysis of form, and success was based solely on mechanical performance or one’s ability to “stay-within-the lines.” The majority of the subject matter consisted of pets, flowers, portraits, and landscapes, and the kits contained the muted colors so popular at the time. The 50’s also saw a return of the Hawaiian craze and during that time nine million ukuleles were produced in one decade. It seems particularly fitting to deliberately merge these two mass-produced, lowbrow trends, superimposing the imagery of one on the other.

I consciously chose images for the ukuleles that were the closest to classical paint-by-number content; bolero dancers, lighthouses, covered bridges, landscapes, kittens, a dog, flowers, and yes, even a nude (woman of course. We are, after all, talking about the 1950’s).

Another important aspect of the ukuleles is the presentation. I purchased a pristine, hand-made wall mount for each ukulele in order to take the ukulele out of the context of the forgotten instrument leaning in the corner of a room, and intentionally elevate it to the status of the pristine art object hanging formally on a white gallery wall. It would be one thing to see an image of one of my painted ukuleles, but quite another to see an image of them mounted as they are.

A final, but less important feature of this body of work is that I was able to locate nine identical ukuleles with a smaller than normal, offset sound hole, thereby allowing me a more continuous painting surface.

Stacy: In your artist statement, you also mention the term “lowbrow” in relation to the ukulele and the paint by numbers style you have adopted. What does this term mean to you, and does it change once the work enters “highbrow” spaces and prices, or is that the point? The term has always felt confusing to me– lost in between earnestness and irony, reminiscent of punk– a hard exterior with a soft shell of longing.

Jenn: There is an actual Los Angeles art movement known as Lowbrow – influenced heavily by comics, sideshow banners, street art, religious art, pulp illustrations, and almost all things pop culture. However, my use of lowbrow refers to all things not highbrow, nonacademic, common, uneducated, bordering on kitsch, hence the “lowly” paint by number painting. And actually, my use of these specific words is almost in passing as a way to address both the paint by number style and the woebegone ukulele.

Stacy: I like what you have to say about the term “lowbrow” being two-folds as a descriptor and also as something larger, a movement. I am familiar with the Lowbrow Movement in Los Angeles, which is maybe why the term feels confusing to me. Lowbrow seems to be everywhere– on billboards, streets, and especially in galleries. There is a pride in it not being highbrow, but there is also an irony in that pride as well.

I guess, and I understand this might be outside of your own intention as an artist, but I was wondering about your perspective on the matter. In general, do you feel the Lowbrow Movement is a revolt against highbrow art? And, if so, then why does it follow the same conventions as highbrow? I know some artists do street art and that is “outside the convention” but eventually I always see the same artists showing at MOCA or selling work for thousands of dollars, many own galleries, etc. I am thinking of Shepard Fairey here. I don’t personally find anything morally wrong with this, and I’m not opposed to it, but I do see the confusion– and I see the content change/shift from environment to environment.

I’m also thinking here of Louise Lawler and her photographs which document art inside different habitats– museums vs. residential homes, and how the placement of art in different environments affects content.

Similarly, how does the new highbrow status and revered regard for Lowbrow work affect Lowbrow’s intention?

Or, maybe a better question would be who owns punk rock? Ha. I hope this makes sense.

Jenn: Well, well.

How does a recliner assume the status of an Eames chair? Or does it? In reference to Louise Lawler and her photographs I don’t personally view a change in content based on environment. A Jeff Koons is still a Koons no matter where it’s placed, just like a paint by number isn’t necessarily kitsch or high academic art based on placement in a living room or placement in a gallery. I believe these pieces change from being inert to intellectually interesting based on the status of the artist who is creating the work.

Reputation can take years to establish and I guess this may turn into a conversation about establishing identity. It’s making a brand for oneself. An artist may start out in the Lowbrow (this word is actually copyrighted by Robert Williams, founder of Juxtapoz) Underground Movement and in a few years they may find themselves in a high-end gallery, still making what they would term as “Lowbrow”, but with a highbrow status.

So in the beginning Lowbrow is similar to any art movement – it’s a reaction to other art around it, and what came before it, trying to be different, yet eventually it makes it’s way into the mainstream, is recognized, and becomes highbrow. The work and it’s content doesn’t necessarily change, only the space in which its placed, as well as the identification of the artist, leading back to Louise Lawler’s work. The environment (person and structure) is changing, not the object.

Stacy: Jenn, I really like your response here. Punk rock owns punk rock. Likewise, Lowbrow owns Lowbrow. An object is an object, unless we call it art, and unless the artist is well known and admired, then we call it an investment. This is what I’m hearing. I certainly see that. However, there is something mystical to me about when art changes location– I see this when I look at Lawler’s photographs– and maybe I should give Lawler’s work more credit for doing this than the concept itself– but when art transitions from the sanctuary (of a gallery or museum) and into a home– I see the artwork itself yawning and waking up from a dream. Likewise, art in the wilderness (on the streets) that moves into a gallery feels too contained, sad or exploited. Ha, I am thinking of art like it’s an Eddie Murphy movie from the 80s! What is that– Trading Places?! Oh, I’m such a weirdo. I know it’s perhaps immature of me, but I can’t stop giving art emotions of my own volition. Do you ever do this, or am I just a lunatic?

Jenn: I’ve been trained, or brainwashed, during my time in academe not to cherish everything. When you have professors who take your art and throw it in the trash, just to teach you that you don’t need to value every damn thing you make, you learn rather quickly to let art go. The reality is that my real connection with my (own) work is in the production of it, that long, often tedious, often unclear path from inception to completion. Once it is complete, the excitement is the next one. However, other objects are a completely different story.

The other day I picked up a bunch of six bananas in the supermarket, took one from the bunch and placed it back on the table. My husband asked me why I took one off and left it behind and I told him that six bananas are too many for two people, we would end up throwing one away, so why not leave it for someone else. He said jokingly that I had just separated that banana from its family and that it was going to begin immediately grieving the loss of its brothers and sisters. I kind of freaked out after he said that. Yes, the banana WOULD BE sad! And then I was sad. I became so sympathetic to the plight of this lonely banana I thought about going back to rescue it, but I also didn’t want to throw it away if we bought too many, and I didn’t want to stuff myself with extra bananas just because I didn’t want that one banana to suffer. I left it in the supermarket, but it was difficult and I left somewhat exhausted. I kept thinking back to the image of that banana pining away on that table. At odd moments I still think I hear the low, mournful cry of an orphaned banana. I still am not sure I made the right decision.

I asked my husband not to tell me what our food was thinking ever again.

So yes, I do this quite often, just never with my own art. For me, as an artist, it’s about making the stuff. It’s the engagement.

Stacy: Tell me more about this engagement and why you make art.

Jenn: I’ve been thinking about how to answer this question without writing a book. The reality is I make art because Little House on the Prairie destroyed my life, but that’s a conversation that would take hours to discuss, and dissect. I am going to reply to your last question with a video response:

Stacy: Oh, this is a wonderful response. Thanks for talking to me, Jenn. By the way, I love the idea of how Little House on the Prairie ruined your life– I’m obsessed with that show, and when I go to the local natural foods store, I feel very happy to scoop grains or nuts into bags and daydream it’s a general store from that era. Oh, but like you said, this is a whole other conversation. I hope to hear more from you and about and your art in the future.

———————————-

See Jennifer Jarnot’s work in person at Leedy-Voulkos Art Center / 2012 Baltimore / Kansas City, Missouri / 64108 / 816-474-1919 / Gallery Hours: Thurs. – Sat. 11 – 5 / Exhibition runs until October 27th. You can also see her work on the web anytime at http://www.jenniferjarnot.com.

Beautiful! http://www.segmation.com