Stacy Elaine Dacheux: Yi and Adrienne, I was so happy to spend the afternoon at LACMA with you. Lately, I have been feeling stagnant, frustrated, or just emotionally tense . . . so, it was just what I needed. As soon as we entered the Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada exhibit, my body relaxed.

Stacy (con.t): I felt happy, fortunate to be in a space with such a thoughtful artist who made work in response to tragedy, with others, in Los Angeles, and beyond into the desert. My first impression of the show was that he did not make rules for himself regarding what he should be. He was a social worker, a furniture maker, and an artist. Although, in one of the videos he does not want to call himself one. He says something like he is always becoming an artist– always becoming, never being. Being an artist means the death of an artist. I wonder what your thoughts are on this statement or what were your first impressions?

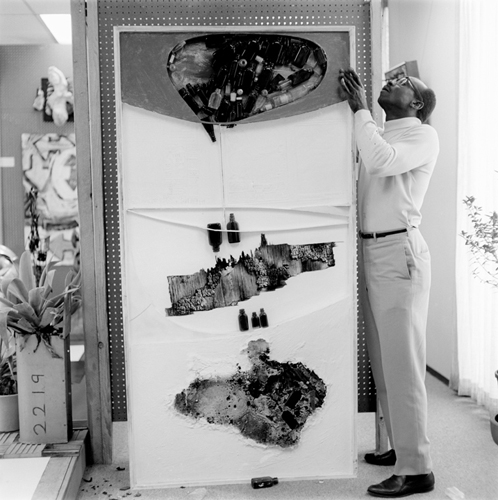

Yi Sheng: Noah Purifoy is my new art hero. When I walked into the show at LACMA, during the first visit a few weeks ago, I felt skeptical. I was hesitant. I had just visited Purifoy’s Outdoor Desert Art Museum, and the potency of his pieces was still very much with me. I was curious to see how his work could stand up to or be changed by the sterility of a museum. Even the title of the show, Junk Dada, made me a little weary. I remembered my experience in the desert just a day before. I was moved by the work; it was messy, scary, playful, lonely, angry, conflicted; a soup of emotions, that were called on. This is gonna sound totally meta, but I could not, not picture him working in that sun battered yard. On every piece that I walked under, and around, stepped inside of and investigated with my head hiding under a scarf, I could imagine him, a man, at the end of his life, working, alone, with a kind of confidence, bravado, humor, and steadfastness towards his desert vision.

Adrienne Walser: When I first saw Purifoy’s art in the Joshua Tree desert, it seemed to belong there–like that landscape was the place of/for his junk-art assemblages. The hot dusty desert was where urban and rural detris could become magical objects and labyrinths. When we wandered around there, Stacy, I didn’t know anything about Purifoy or his life–I didn’t know he was old when he created such exuberant work, and I didn’t know he’d grown up in Birmingham to sharecropper parents, that he was African-American, and I didn’t know he was the founding director of the Watts Tower Center and that in 1965 he’d created an art exhibition with other Los Angeles artists out of burned remnants from the riots in the community of Watts–66 Signs of Neon.

Adrienne (con.t): When I saw that particular exhibit at LACMA, I understood that in his Joshua Tree art he’d returned to a way of working and making that he’d begun early in his career. In retrospect, I see how the assemblage sculptures in Joshua Tree are evidence of Purifoy’s feeling of always becoming an artist, always becoming, never being. There his art felt frenetic; he was compelled even as an old man to keeping working–in the heat of the desert sun–to keep imagining and creating. It was spectacular. I loved the assembling of throw-away objects into fantastical urban structures.

Adrienne (con.t): Like you Yi, I felt hesitant about seeing this work in a museum space. I am curious to know more about what felt scary and lonely to you out in Joshua Tree, and what you both think happened (or didn’t) when those assemblages showed up inside the white clean walls of LACMA.

I wondered how they would fit there and why they needed to be there. I felt that something would be lost, and that his work, his art, should be for those who seek it out in difficult places…

Maybe this is why I didn’t spend as much time looking at those pieces and spent more time with the 66 Signs of Neon exhibit and his art from the 80s and 90s, which blew me away–the craftsmanship, color, materials, uniqueness.

Stacy: Yi and Adrienne, yeah it’s interesting to think about context and expectation. Adrienne, I remember seeing Purifoy’s work in the desert with you. How it felt like a big art playground– interactive and alive. I am really attracted to artists who make work in different environments regardless of anticipation. Yi, I want to know more about why he is your new art hero. What qualities make him heroic– is it in the work itself, the life, or both? At the exhibit, I remember you were especially interested in his environmental work at Brockman Gallery.

Stacy (con.t): The press release for that show states, “Mr. Purifoy has put together an environmental show describing the conditions under which culturally deprived people live. His art is used to make people conscious of conditions and environments, and tries to bring to people certain conditions which exist at large.”

I wonder if you want to speak more to that part of the collection– what you wanted to see, what was missing, why you were drawn there?

Yi: I admire artists who can make work consistently throughout their lives, especially when it seems like no one is looking or even cares. I can’t think of a more isolated condition for making art than living in the desert! Artists have to find a way to continue to make work in light of a harsh reality; outside of school, no one cares what you do and what you make. No one is looking at all.

Yi (con.t): But, when art happens, and so consistently and with so much urgency, it is really amazing, and worth taking note. In Noah Purifoy’s case, early in his career, he gained some fame with his touring show, 66 Signs of Neon, but then he made a decision to put his art career on hold to serve the city of LA, founding community arts programs, heading art councils, and protecting the Watts Towers. His adult life was dedicated to promoting art, and to me, he sacrificed his creative energy, to serve art. He didn’t get to fully focus on his work until the last 15 years of his life! But when he got to work, it felt like he unleashed all the energy that he had been saving. The work out in the desert is full of energy and presence.

Yi (con.t): I also felt the exuberance that Adrienne mentioned in the desert works; they seems to be made with a kind of carefreeness and unabashed confidence. It is his attitude of “always being” that lends to a presentness in his desert works. To “be an artist” is to be concerned with what or how others require of the work for him to have the title of “artist”. The latter pieces feel present, they are less concerned with art historical lineage. A stark contrast in style compared to his earlier, more carefully, “artfully” assembled sculptures and wall pieces.

Yi (con.t): In regards to the Brockman Gallery show, there’s a small side room within the Purifoy exhibition space. In contrast to the sculptures occupying the main exhibition space, there’s about a dozen small photos, modestly framed. They are documentations of a solo show, an immersive environment that Purifoy created for the Brockman gallery in 1971. It’s easy to miss the section entirely (which I did during my first visit) but pay a little more attention and I think this room reveals a politically provocative Purifoy (contrary to his claim that his work is not political) Purifoy created an overcrowded and dysfunctional family of 11, living in a squalid apartment, complete with roaches and vermin crawling all over the place, food rotting in a refrigerator, and what looks like 2 people doing it under the sheets. Whoah wow, I was blown away by just the description on the didactic. The pictures on the wall barely captures what must have been show rife with social implications. Oh and get this, the show was titled “Niggers Ain’t Gonna Never Ever Be Nothin’—All They Want to Do Is Drink and Fuck.”

Adrienne: That particular 1971 installation at the Brockman Gallery followed his 66 Signs of Neon Show (Rubbish assembled from the fires of the Watts Riot) and his Watts Tower Workshop. As you note, Yi, it was a difficult piece, which I read as a critique of assumptions and stereotypes of African-American life at that time; such a brutal display in an art gallery would no doubt provoke. That he installed this in an art gallery in 1971 illuminated for me the politics of his art practice.

I want to think about this notion of Purifoy as artist–or as not an artist; I see him as an artist very much connected to art lineages and traditions; all the phases of his body of work are in conversation with social and cultural issues and with art history. In this way, his work appears to me as “art historical,” even as he revised and re-imagined what are to me recognizable aesthetic forms; his use of particular original material, or found material, from African-American culture and locations, and his interest in art as a social tool “to change people” is what perhaps makes him seem more than an artist? Or doing more than being an artist?

Adrienne (con.t): Purifoy was trained in art schools. This seem important to acknowledge: that while his work may operate in some ways as outsider art, given his commitment to African-American history and culture, he spent much of his career working with other artists and inspired by art historical movements. For example, he created the modernist Bed “Headboard” in 1958 after attending Chouinard Art Institute (now Cal Arts) and as he worked creating store window displays, eventually working with one of the first accredited African-American interior designers.

Adrienne (con.t): The pieces in this LACMA show from 1988–”Urban Sprawl,” “Office Chair,” and “Black, Brown and Beige (After Duke Ellington)”–are intricate handcraftsmanship meets urban modernist design meets Dada assemblage art. I see his Junk Dada desert art as inspired to some degree by his exposure to the early 20th century Dada aesthetic; maybe what makes that body of work so unique, so much seemingly a unique genius vision, is that he is working with materials and history that are simultaneously urban and rural, and about places, people, and events that haven’t historically been significantly present in art galleries and museums.

It wasn’t my impression that no one was looking or caring about Purifoy’s work. Based on his bio, from 1960 to 2011 Purifoy was in a solo or group show every year–sometimes more than one–all over the country, although primarily in Southern California. He never stopped making art, and he was more often than not showing at a gallery or college museum, and often in group shows. And yet, as he himself says, and what we are curious about, is his ability to move fluidly between hands-on art-making, creating learning opportunities for people, and doing community service work. Yi, you write that he “sacrificed his creative energy to serve art,” but I wonder if for Purifory that his art-making happened as he was working in communities serving people and art, and that that is what fed and furthered his creative energy.

Stacy: I love the conversation here. Adrienne, I know what you are saying. From my understanding of the exhibit, Purifoy comes across as a person who used art to connect with other people– to not only express but activate awareness, which is interesting because his work doesn’t feel pedantic to me. I think he trusts the materials in this way. He trusts that debris has meaning. He trusts in the material’s ability to tell half stories. His juxtaposition of these half stories generates art and awareness, be it in assemblages or environments.

Stacy (con.t): I also like how he sees environment as an extension of identity or a lens through which we view not only ourselves, but our home in the world, be it inside an art museum or outside in the desert. As far as Yi’s thoughts on Purifoy’s ability to serve art more so than create it after the 66 Signs of Neon show, I think maybe what she means is that he could have been more ambitious as an art star, focusing only on solitary output and gallery showings. Instead, he split his energy into the city and other people. This choice is admirable because it is not in line with traditional high art careerism. He carved his own path and trusted his own intentions with art. In other words, his focus was not centered only on the gallery– that was just one of his lenses. This is an important aspect to consider because I don’t think he could have made work with the same heartbeat otherwise. His tenure in the desert is fascinating because it feels like a departure, yet the LACMA exhibit hints that he made community there too.

Stacy (con.t): “From the Point of View of the Little People” (1994) shows a series of legs, collected in a row, seemingly standing on a gallow.

The LACMA exhibit showcases this piece in addition to a photo of the piece as it exists in the desert. Under the photo, it states, “Driving through the desert in his Ford pickup, Purifoy formed friendships with residents of Joshua Tree who were eager to get rid of belongings. The objects would become part of assemblages such as this work, which also utilizes its items purchased at swap meets in the area. ‘You’d be amazed at the stuff that is exchanged there, because it’s stuff that people in Los Angeles throw away.’ Purifoy recalled. ‘They recycle here, resell, because everyone is in a state of developing something here. It’s pioneer county.’”

Adrienne, I remember us experiencing the piece in the desert, as a small part of a larger construct or village. I loved the way the air felt out there. I loved the way the sun was so hot, I kept trying to find shelter beneath the work, in its shadows. There was something about the elements that made the work feel alive and haunting– childlike.

At LACMA, the same piece becomes a quote from a larger story. We lose the village, but we gain historical context, which is valuable too. I appreciate how LACMA allowed me to see Purifoy as an artist and person– not just a remnant. I still have so much to learn about how various people look at art and artmaking. Thanks for going to the exhibit with me! Any last final thoughts?

Stacy: Yi, I love listening to you and Adrienne discuss art. Maybe we should resume this conversation at a later date, maybe reporting from the desert this time instead of the gallery? I love the idea of that.

Visit the Noah Purifoy Foundation for more information on visiting his Outdoor Desert Art Museum.

The “Junk Dada” LACMA exhibit runs from June 7, 2015 – September 27, 2015.

—————————–

Adrienne Walser is always out and about with her friends looking at art in Los Angeles–her home city of ten years. She is a contemporary art writer and a modernism scholar, who has written about early twentieth-century travel poetics and queer feminist Dada. Her current academic project is on The Little Review and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She is also working on a non-fiction project on the body, intimacy, and loss. She is a Literature faculty member for the Bard College MAT program in Los Angeles that prepares graduate students to become History and English teachers in high-needs public schools.

Stacy Elaine Dacheux is the curator of this website. She enjoys seeing art with Adrienne and Yi!

Oh bud. Your curious adventures make me miss LA and you something terrible. Loved reading this.

Oh, bud! The library is not the same without your incredible spirit! I hope to visit NYC and see art with you sometime soon! That would be a delight! xoxoxox! LOVE YOU!